The

most comprehensive study of personal wealth ever undertaken also

reports that the richest 1% of adults alone owned 40% of global assets

in the year 2000, and that the richest 10% of adults accounted for 85%

of the world total. In contrast, the bottom half of the world adult

population owned barely 1% of global wealth.

The

research finds that assets of $2,200 per adult placed a household in

the top half of the world wealth distribution in the year 2000. To be

among the richest 10% of adults in the world required $61,000 in

assets, and more than $500,000 was needed to belong to the richest 1%,

a group which — with 37 million members worldwide — is far from an

exclusive club.

The

UNU-WIDER study is the first of its kind to cover all countries in the

world and all major components of household wealth, including

financial assets and debts, land, buildings and other tangible

property.

‘One

should be clear about what is meant by “wealth”,’ say co-authors

James Davies of the University of Western Ontario, Anthony Shorrocks

and Susanna Sandstrom of UNU-WIDER, and Edward Wolff of New York

University. ‘In everyday conversation the term “wealth” often

signifies little more than “money income”. On other occasions

economists use “wealth” to refer to the value of all household

resources, including human capabilities.’

‘We

use the term in its long-established sense of net worth: the value of

physical and financial assets less debts. In this respect, wealth

represents the ownership of capital. Although capital is only one part

of personal resources, it is widely believed to have a

disproportionate impact on household wellbeing and economic success,

and more broadly on economic development and growth.’

Wealth

levels across countries

Using

currency exchange rates, global household wealth amounted to $125

trillion in the year 2000, equivalent to roughly three times the value

of total global production (GDP) or to $20,500 per person. Adjusting

for differences in the cost-of-living across nations raises the value

of wealth to $26,000 per capita when measured in terms of purchasing

power parity dollars (PPP$).

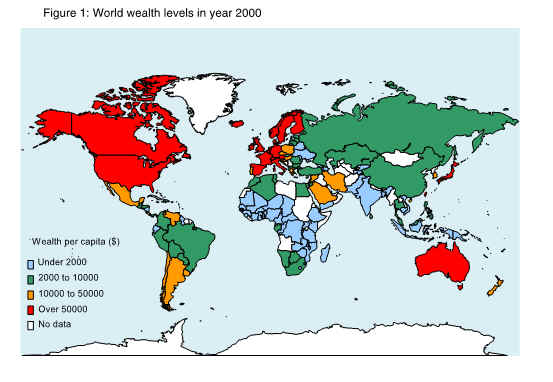

The

world map shows per capita wealth of different countries.

Average wealth amounted to

$144,000 per person in the USA in year 2000, and $181,000 in Japan.

Lower down among countries with wealth data are India, with per capita

assets of $1,100, and Indonesia with $1,400 per capita.

Average wealth amounted to

$144,000 per person in the USA in year 2000, and $181,000 in Japan.

Lower down among countries with wealth data are India, with per capita

assets of $1,100, and Indonesia with $1,400 per capita.

Per

capita wealth levels vary widely across countries. Even within the

group of high-income OECD nations the range includes $37,000 for New

Zealand and $70,000 for Denmark and $127,000 for the UK.

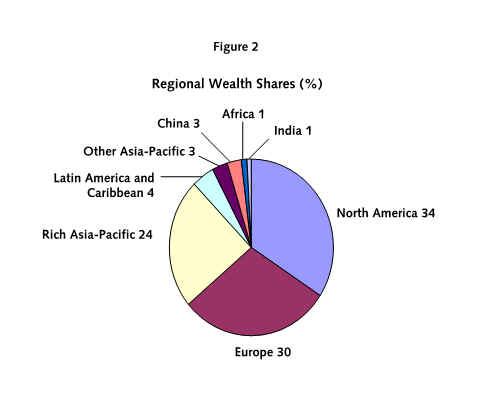

Wealth

is heavily concentrated in North America, Europe, and high income

Asia-Pacific countries. People in these countries collectively hold

almost 90% of total world wealth. (Figure 2)

Although

North America has only 6% of the world adult population, it accounts

for 34% of household wealth. Europe and high income Asia-Pacific

countries also own disproportionate amounts of wealth. In contrast,

the overall share of wealth owned by people in Africa, China, India,

and other lower income countries in Asia is considerably less than

their population share, sometimes by a factor of more than ten.

(Figure3)

The

study finds wealth to be more unequally distributed than income across

countries. High income countries tend to have a bigger share of world

wealth than of world GDP. The reverse is true of middle- and

low-income nations. However, there are exceptions to this rule, for

example the Nordic region and transition countries like the Czech

Republic and Poland.

The

authors of the UNU-WIDER study explain that in Eastern European

countries ‘private wealth is on the rise, but has still not reached

very high levels. Assets like private pensions and life insurance are

held by relatively few households. In the Nordic countries, the social

security system provides generous public pensions that may depress

wealth accumulation.’

World

wealth inequality

The

concentration of wealth within countries varies significantly but is

generally high. The share of the top 10% ranges from around 40% in

China to 70% in the United States, and higher still in other

countries.

The

Gini value, which measures inequality on a scale from zero to one,

gives numbers in the range from 35% to 45% for income inequality in

most countries. In contrast, Gini values for wealth inequality are

usually between 65% and 75%, and sometimes exceed 80%.

Two

high wealth economies, Japan and the United States, show very

different patterns of wealth inequality, with Japan having a wealth

Gini of 55% and the USA a wealth Gini of around 80%.

Wealth

inequality for the world as a whole is higher still. The study

estimates that the global wealth Gini for adults is 89%. The same

degree of inequality would be obtained if one person in a group of ten

takes 99% of the total pie and the other nine share the remaining 1%.

Where

do the world’s wealthy live?

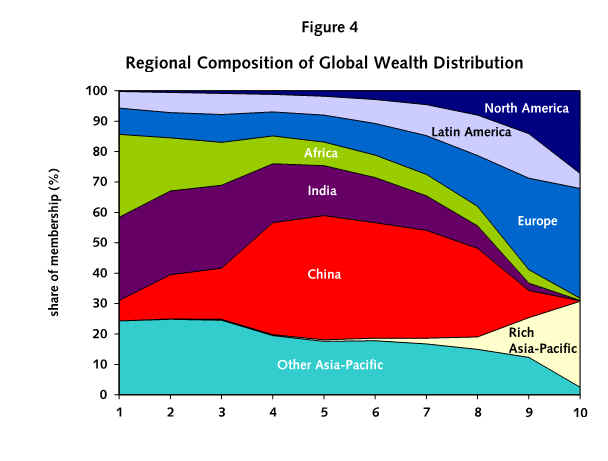

According

to the study, almost all of the world’s richest individuals live in

North America, Europe, and rich Asia-Pacific countries. Each of these

groups of countries contribute about one third of the members of the

world’s wealthiest 10%.

(Figure

4)

China

occupies much of the middle third of the global wealth distribution,

while India, Africa, and low-income Asian countries dominate the

bottom third.

For

all developing regions of the world, the share of population exceeds

the share of global wealth, which in turn exceeds the share of members

of the wealthiest groups. (Figure 3)

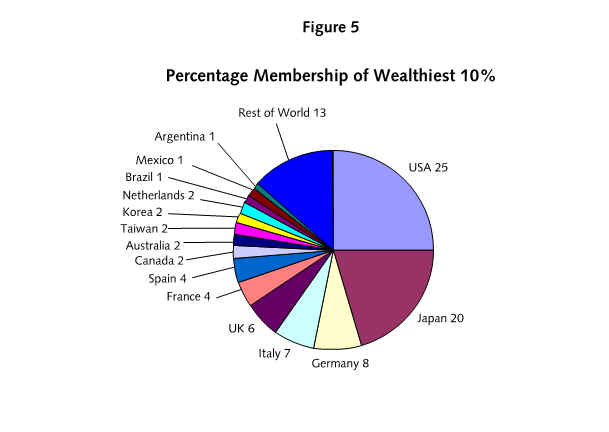

A

small number of countries account for most of the wealthiest 10% in

the world. One-quarter are Americans and another 20% are Japanese.

(Figure 5)

(Figure 5)

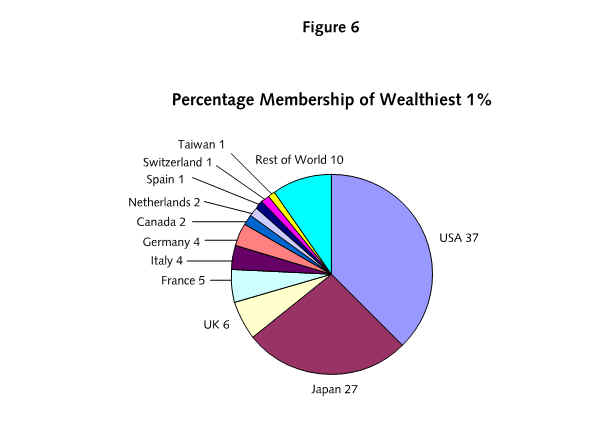

These

two countries feature even more strongly among the richest 1% of

individuals in the world, with 37% residing in the USA and 27% in

Japan.

(Figure

6)

According

to Anthony Shorrocks, a country’s representation in the rich

person’s club depends on three factors: the size of the population,

average wealth, and wealth inequality.

‘The

USA and Japan stand out’, he says, ‘because they have large

populations and high average wealth. Although Switzerland and

Luxembourg have high average wealth, their populations are small.

China on the other hand fails to feature strongly among the super-rich

because average wealth is modest and wealth is evenly spread by

international standards. However, China is already likely to have more

wealthy residents than our data reveals for the year 2000, and

membership of the super-rich seems set to rise fast in the next

decade.’

Composition

of household wealth

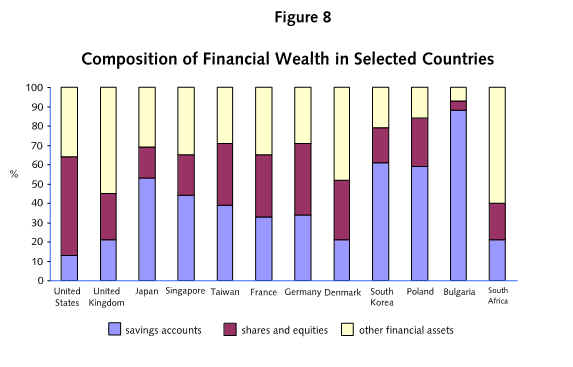

The

UNU-WIDER study shows major international differences in the

composition of assets, resulting from different influences on

household behaviour such as market structure, regulation, and cultural

preferences.

Real

property, particularly land and farm assets, are more important in

less developed countries. (Figure 7)

This reflects not only

the greater importance of agriculture, but also immature financial

institutions.

The

study also reveals striking differences in the types of financial

assets owned. Savings accounts feature strongly in transition

economies and in some rich Asian countries, while share-holdings and

other types of financial assets are more evident in rich countries in

the West.

According

to the authors of the UNU-WIDER study, savings accounts tend to be

favoured in Asian countries because ‘there appears to be a strong

preference for liquidity and a lack of confidence in financial

markets. Other types of financial assets are more prominent in

countries like the UK and USA which have well developed financial

sectors and which rely heavily on private pensions.’

Surprisingly,

household debt is relatively unimportant in poor countries. As the

authors of the study point out: ‘While many poor people in poor

countries are in debt, their debts are relatively small in total. This

is mainly due to the absence of financial institutions that allow

households to incur large mortgage and consumer debts, as is

increasingly the situation in rich countries’

The

authors go on to note that ‘many people in high-income countries

have negative net worth and—somewhat paradoxically—are among the

poorest people in the world in terms of household wealth.’

Authors

of The World Distribution of Household Wealth, December 2006

James

Davies

is a Professor, and the RBC Financial Group Fellow, in the Department

of Economics at the University of Western Ontario. He is the Director

of the UNU-WIDER project on Personal Assets from a Global Perspective.

jdavies@uwo.ca

Susanna

Sandström

is a Research Associate at UNU-WIDER. She has previously held

positions at the Luxemburg Income Study and Statistics Finland. sandstrom@wider.unu.edu

Anthony

Shorrocks

is the Director of WIDER and has previously held positions at the LSE

and University of Essex. shorrocks@wider.unu.edu

Edward

Wolff

is Professor of Economics, New York University, Senior Scholar, Levy

Economics Institute of Bard College, and Research Associate, National

Bureau of Economic Research. edward.wolff@nyu.edu

To

attend the launch, please register:

In

London:

Francesca

Pompili, Media Services Manager

The

Foreign Press Association

11 Carlton House Terrace

London SW1Y 5AJ

Telephone: +44 (0)20 7930 0445

E-mail: francescapompili@foreign-press.org.uk

In

New York:

United

Nations Secretariat

Press

Room S-226

46 Street & 1 Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Jin Zhang, Programme Assistant

United Nations University office in NY

Telephone: +1-212-963-6387

E-mail: jin@ony.unu.edu

Figures: